How the card game "Set" is a Case Study on what is missing from mathematics education

Published on 5-Apr-2021 -- Last updated on 5-Apr-2021

Perhaps I am a bad loser, but I often find myself ranting about how "bad"

certain games are. While most games are entertaining in some way, there are a

lot of games which provide zero depth and can be figured out in a matter of

minutes. Games of which the optimal strategy or style of play exposes itself

easily. What follows is either totally inconsequential gameplay or one depends

almost entirely on luck. One classic conceptual example is the game of

Tic-Tac-Toe.

Take a look at how to make Tic-Tac-Toe

inconsequential

Learning one simple strategy can make Tic-Tac-Toe unlosable. More complex games

such as chess and go — which cannot be figured out within minutes —

are not only interesting for a longer time, but also raise a lot of interesting

intellectual questions because of their depth. Questions which can only be

answered by applying a core concept of mathematics: breaking down a problem

into problems our brain can actually handle. I want to cover this concept by

looking at the card game of Set, have a look at why this is such a generally

valuable skill and pose a question on why it is missing from our ordinary

education.

A few weeks ago I was playing the card game

Set

Play Set

versus a computer

with one of

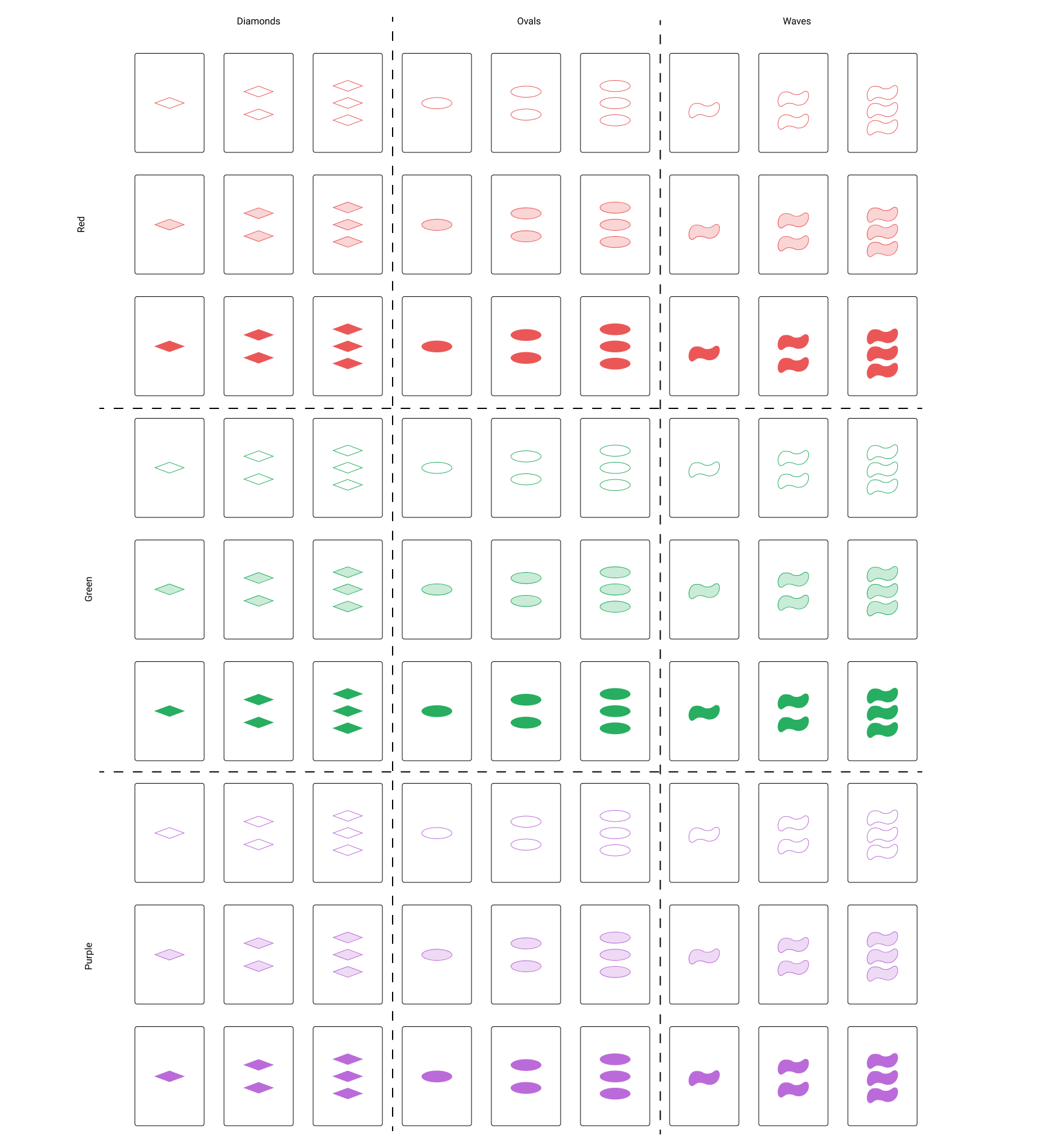

my flatmates. For everyone not familiar with this game: there are 81 cards

containing with one, two or three of 1 of 3 different shapes (diamond, oval,

wave), with 1 of 3 colours (red, green, purple) and 1 of 3 shadings (solid,

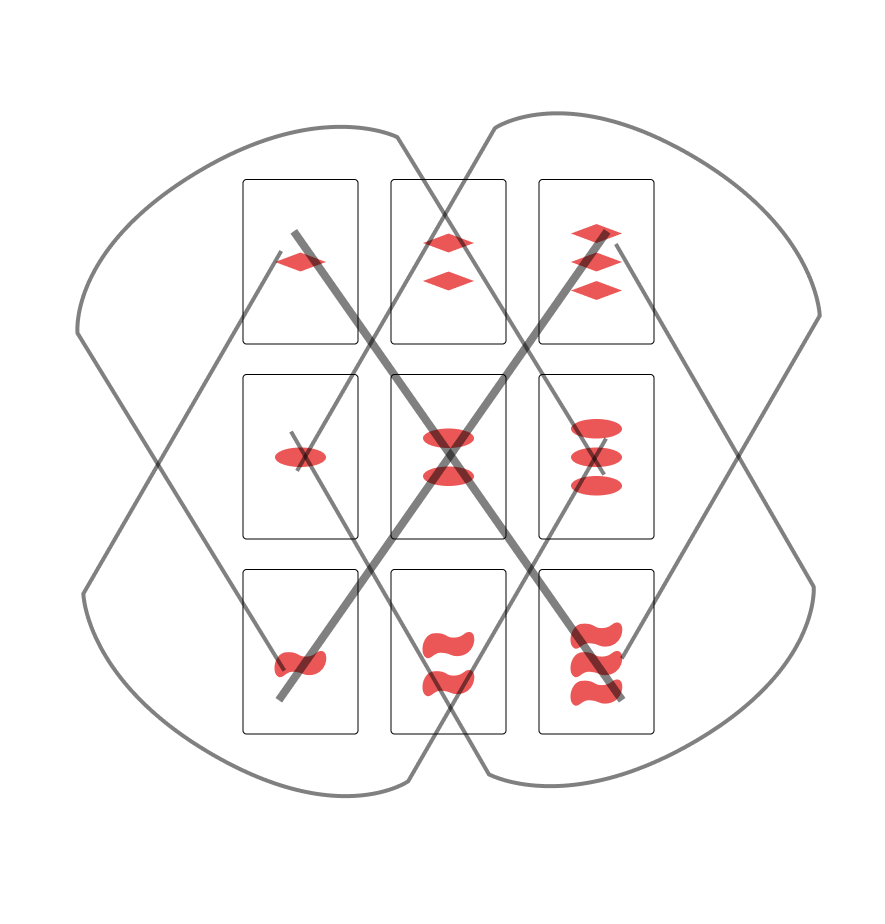

dotted, open). All of these cards can be seen in Figure 1. The game

starts with 9 random cards on the table and the goal is to find a "set": a pair

of three cards which of every of the four properties specified contains either

three different variants of that type or three of the same variant of property.

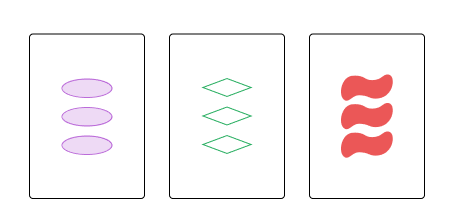

For example, for the set in Figure 2 all cards contain the same 3

shapes, but these shapes are all different, their shading is all different and

the colour is all different. Thus this is a valid set. If there are no sets on

the table you add a new random card and you repeat. Whilst this explanation may

seem rather complicated, the actual game is rather simple to grasp. In contrast

to most games, however, Set is based purely on skill. How fast can one go

through all combinations of cards? Although there are some shortcuts one can

take, in the end, it all comes down to who can focus for the longest time and

find a set first.

Whilst playing Set, we had some (we thought at the time) quite rare odds, and had to go all the way up until 14 cards for us finally get a possible set. Afterwards, my roommate — who is in no way a mathematician — asked the question of how many cards it would take to always have a set within those cards. So we thought about, concluded our brains couldn't handle thinking about 4 properties with 3 options each and attempted to create the largest number of cards without a set. We hoped the intrinsic beauty of mathematics and all its symmetries would make it such that our solution would also be the answer (when added one) to the first problem. After some fiddling we came to the answer of 19. Quite happy with our answer we googled the solution and found — to our disappointment — that our answer was incorrect (the actual answer is 21). It turned out to be a reasonably well known problem also known as the Cap set problem.

After reading about the cap set problem a bit, I was captivated by its solution. Partly, because it involved subject matter from a university course I am currently following, but more so because of the beautiful visualization it relies on for its solution. So if you want to read about it on the wikipedia page, please do. But I want to go over it, because it shows us something about mathematics which isn't taught in most schools.

Visualizing Set

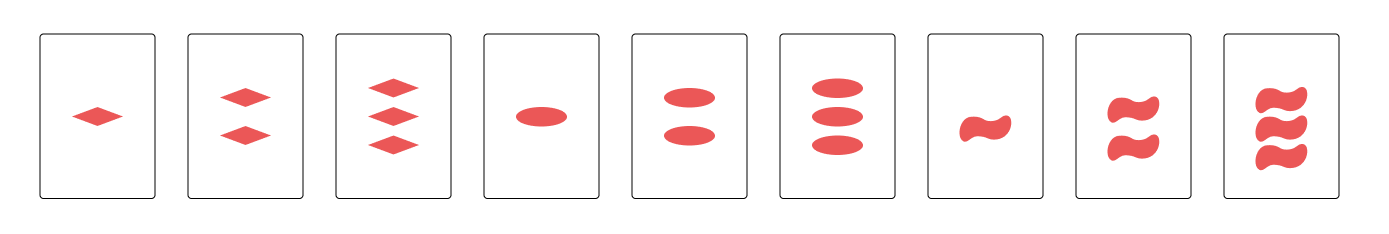

So let us start with a simpler game, a game which only involves 9 cards. Each card having one, two or three of 1 of 3 shapes, but all cards are red and have a solid shading. Let us call this game "Subset" of which the cards can be seen in Figure 3. You can get a "Subset" by again getting three cards which for all properties either belong to different variations of that type or the same variation of that type. This is a way simpler game. So let us try to answer the same question for "Subset" as we posed for "Set": How many cards can we have before we are guaranteed to have a "Subset"?

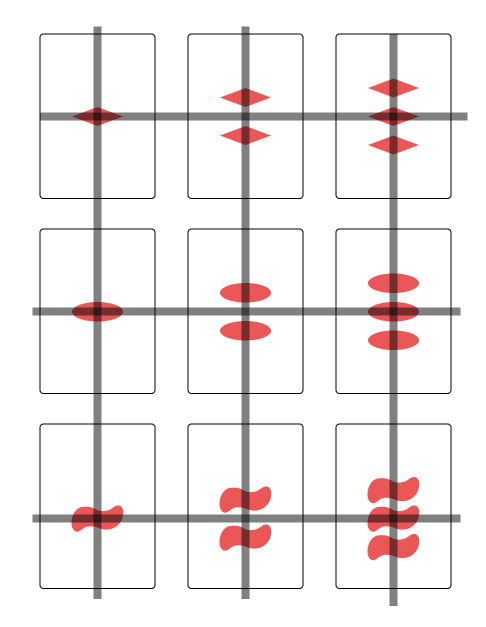

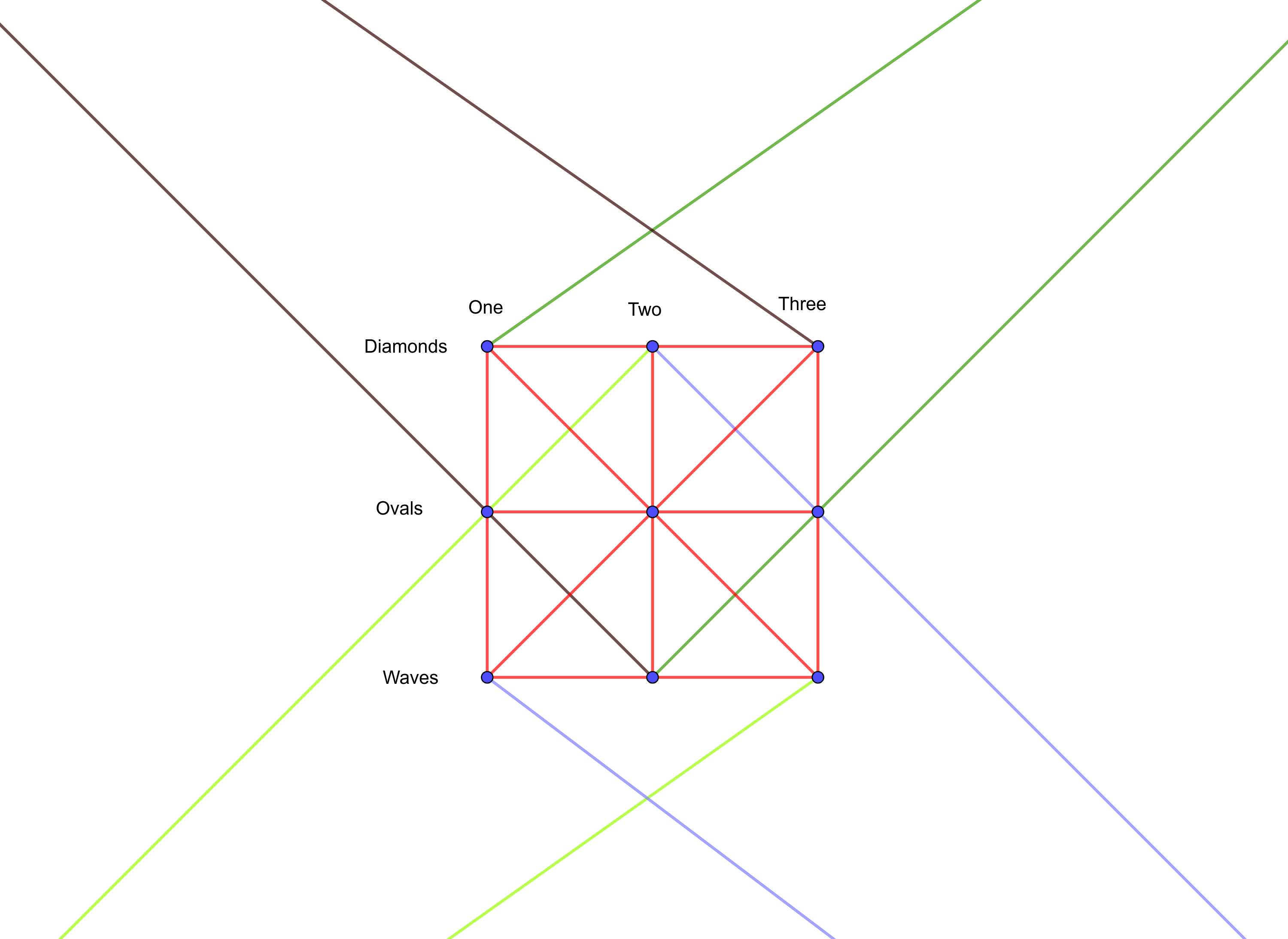

Asking this question even for the simpler game of "Subset" is quite overwhelming so we might ask whether there is a similar problem to which we can (more easily) find the answer. You may look at all the cards and put them in a 3 by 3 grid. After looking at this grid for a while you may notice something: all of the rows and columns are subsets as can be seen in Figure 4. Whilst this seems like a good start after looking a bit further you notice that there are some subsets which aren't a row or column of the grid. Then after some more looking you might notice that subsets which aren't a row or column also have a pattern, as can be seen in Figure 5. This turns out to be all the possible subsets.

This already looks proposing, but let us remove even more distractions from the problem. Now that we noticed that we can represent the subsets by drawing lines through the cards, we can just represent the cards with dots. We still have a 3 by 3 grid, but we can just remove some visual-noise from our picture. This can be seen in Figure 6. Now we ask our question again, but in a different way: How many dots can we mark without one of our lines passing through only marked dots. The question is a lot more comprehensible and even better, we are able to visualize our problem.

From just some trial and error, you can notice that you can only mark four dots without there being a line containing solely marked dots. For example, we can mark the 4 corner dots, without one of the lines of Figure 4 or Figure 5 containing only marked dots. If you need to, look at the pictures for a second a try finding another set of for marked dots, which contains no fully marked lines. Because there is no combination of 5 marked dots, for which we don't have a marked line, and dots are analogous to cards and lines to sets, the minimum amount of cards for a subset to show up is five. We can now extend this problem to three properties — creating a new game also having different colours or shading — and we will notice that we can create a similar breakdown and visualization of our problem. This time containing a three dimensional grid. Then we can extend that problem with yet another property.

What we can learn from this?

Whilst this individual problem is interesting to some. To others, who aren't as captivated by abstract problems, this may seem like a total waste of time. To the latter of whom I would tell the following. Shortly and first of all, this problem is actually quite common. While it is used in some technological applications, namely setting the upper bound for how fast we can do matrix multiplications. It is actually a problem of which we encounter similar variations reasonably often.

We as humans love to categorize items and it turns out that most of the time there is also some relationship between these categories. Take people for example — when ignoring a lot of social complexities — can be either be friendly to, neutral to or disliking of a certain person. People can use a Android, Apple or (if that is even still a thing) a Windows phone. They can — when again ignoring a lot of complexities — be more interested in exact, societal or human mind subjects. This problem can be put to use when we want to deal with combining relationships lot of categories on the same set of subjects (in this case people).

More importantly, the approach taken to make the Cap Set problem more manageable, is something which can be applied everywhere and is in fact not only a core part of mathematics but also of most of the other exact sciences. When people say "At university you don't learn a subject, you learn a way of thinking", for this exact sciences, this is mostly what (I would assume) they mean. Most often this takes the form of models and sub-problems. Our 3 by 3 grid of dots and lines is a model of "Subset" which is a sub-problem of the problem we actually posed. We are replacing our problem with a smaller problem which has very similar properties. The king of the models is forming a problem which is equivalent to the original problem. That is to say that a solution to the original problem also applies to the model and a solution to the model also applies to the original problem.

Usefulness of sub-problems and models

Our monkey-brains are extremely amazing, but they have cognitive limits. When we

calculate 12 times 9 in our heads, most people will have difficulty not

performing this as 12 times 10 minus 12 which is equal to suffixing a 0 to 12

and subtracting 12. We divide a relatively easy calculation into multiple steps

instinctively because we cannot handle even simple processes within one step.

Contrary to what one might think, this is not actually an issue. We can perform

all of our cognitive processes in steps or reduce them to similar problems we

can more easily comprehend.

An algorithm literally called

divide-and-conquer

Sometimes this requires the aid in memory which paper or

a computers provide. Sometimes this can be completed solely in our own memory.

So what is the problem? We clearly know how to divide and reduce our cognitive

stress. Well... there lays the problem. Whilst we may learn to perform some of

these steps unconsciously. People — especially when put outside of their

field of interest — totally forget this is a thing. Empirically speaking,

I am always blown away when people try to learn mathematics through pure

definitions or theorems. They might even think that most topics within

mathematics are abstract and have either no or little application or

visualization. Similarly, when people think about programming think it must be

some incredible cognitively heavy process. Don't get me wrong, sometimes it

might be. Most of the time, however, if you have a lot of trouble visualizing

your solution to some programming problem, you are plainly doing it wrong.

Read about "Black Boxes" in computer science

Dividing and reducing a problem into "trivial" steps is the skill.

Everything we perceive as valuable is made up of models and sub-problems.

Those models and sub-problems are again made up models and sub-problems.

Renovating a house? You might think of all list of tasks (sub-problems)

which need to happen in a particular timeline sorted by importance (model).

The absurd thing is that we do this so much in our everyday lives, but consciously applying this process is a huge skill. Most intellectual work however requires us to be aware of the process, since forming models and sub-problems (mostly) won't come instinctively there. This requires experience and training in that field, but can be hugely aided by awareness of this process.

Education

Currently, western-education is focussing on substance over process. This in itself is not a problem. Substance is vastly important because we need a basis to state (and hopefully solve) our problems. We must not forget the goal however. Students need to learn to solve their own problems. It doesn't matter if this problem concerns mathematics or history. The best weapon we have to solve problems are models and sub-problems and schools rarely (if ever) try to teach students to form or utilize these deliberately.

Of course, I am simplifying a lot here. Education curricula are very complicated and I am not an expert on education curricula. My perspective is that of a student of the Dutch schooling system. I am assuming most points also (partly) hold for most other Western schooling.

I think the best place for this is the mathematics curricula. I love mathematics

and even I must admit that the way I was taught it in high school is reasonably

sad. Not due to teachers, but the cause is the amount of subject matter which

needs to be crammed into students who have no clue on how or why to the use it.

This has been a longstanding criticism for mathematicians and

non-mathematicians alike. The popular mathematics 3Blue1Brown

Watch a perfect example of this process from 3Blue1Brown

channel often talks

about how formal mathematics education focuses solely on the definitions and

theorems and therefore shifts away from what our cognitive abilities

instinctively handle. I would go as far as to argue that mathematicians as

of now has little to no significance to most students as far as the goal of

them solving their own problems. I would plead for part of this endless

stream of formalisms — at least at the high school level — to be

replaced by lessons in consciously forming and utilizing models and

sub-problems from everyday or more complex problems.

Our education needs to teach its students to consciously perform the process of utilizing and creating models and sub-problems. This process is used everywhere and is something which will uncloak a lot of the solutions to bigger problems in one's work and even the wider world. Since this is already a core part of mathematics and mathematics leaks a clear goal at the moment, this would be the perfect place to teach it. This way if someone ever asks you some burning question about a proper game, you might be able to find the actual answer without googling for it.